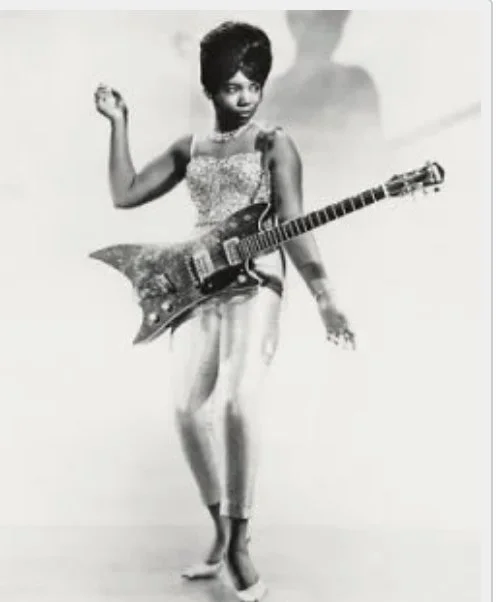

Soul guitar pioneeress Peggy Jones “Lady Bo” who cut her teeth playing with Bo Diddley

Hannah Huxley, England 1832

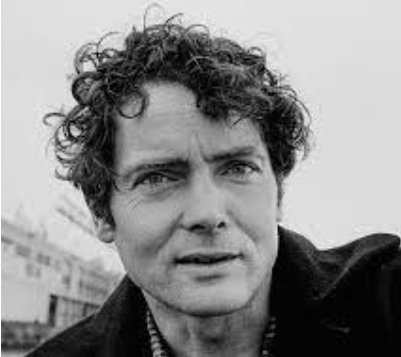

Poet W.S. Merwin

“227 Waverly Place

When I have left I imagine they will

repair the window onto the fire escape

that looks north up the avenue clear

to Columbus Circle long I have known

the lights of that valley at every hour

through that unwashed pane and have watched with no

conclusion its river flowing toward me

straight from the featureless distance coming

closer darkening swelling growing distinct

speeding up as it passed below me toward

the tunnel all that time through all that time

taking itself through its sound which became

part of my own before long the unrolling

rumble the iron solos and the sirens

all subsiding in the small hours to voices

echoing from the sidewalks a rustling

in the rushes along banks and the loose

glass vibrated like a remembering bee

as the north wind slipped under the winter sill

at the small table by the widow until

my right arm ached and stiffened and I pushed

the chair back against the bed and got up

and went out into the other room that was

filled with the east sky and the day replayed

from the windows and roofs of the Village

the room where friends came and we sat talking

and where we ate and lived together while

the blue paint flurried down from the ceiling

and we listened late with lights out to music

hearing the intercom from the hospital

across the avenue through the Mozart

Dr Kaplan wanted on the tenth floor

while reflected lights flowed backward on the walls.”

“Why do we build the wall?

My children, my children

Why do we build the wall?

Why do we build the wall?

We build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

How does the wall keep us free?

My children, my children

How does the wall keep us free?

How does the wall keep us free?

The wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

Who do we call the enemy?

My children, my children

Who do we call the enemy?

Who do we call the enemy?

The enemy is poverty

And the wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

Because we have and they have not!

My children, my children

Because they want what we have got!

Because we have and they have not!

Because they want what we have got!

The enemy is poverty

And the wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

What do we have that they should want?

My children, my children

What do we have that they should want?

What do we have that they should want?

We have a wall to work upon!

We have work and they have none

And our work is never done

My children, my children

And the war is never won

The enemy is poverty

And the wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

We build the wall to keep us free”

Anais Mitchell’s head on tackle of the immigration dilemma is one of the most expertly crafted works I have run across. It’s yet another shining example of how a three minute plus piece can lay bare a complex issue. The song structure builds from the poignant rhetorical questions posed by narrator Greg Brown as a yearning female chorus attempts to weave back answers to them. The dialogue’s atmosphere is brooding and shadowed by uncertainty.

Perhaps her careful repositioning of the relationships between the enemy, poverty, work, freedom, children and wall building allow us to see each in a new way. Which of them is the largest elephant in the room? But in her diorama we can experience a place to examine both how they influence one another and how their interplay might be different. Music often provides such testing grounds . A setting to simplify, maybe the skills to learn when to duck, or draw back the curtain of obfuscation. So if this is an issue of interest to you, give this formidable contribution to solving it a few listens.

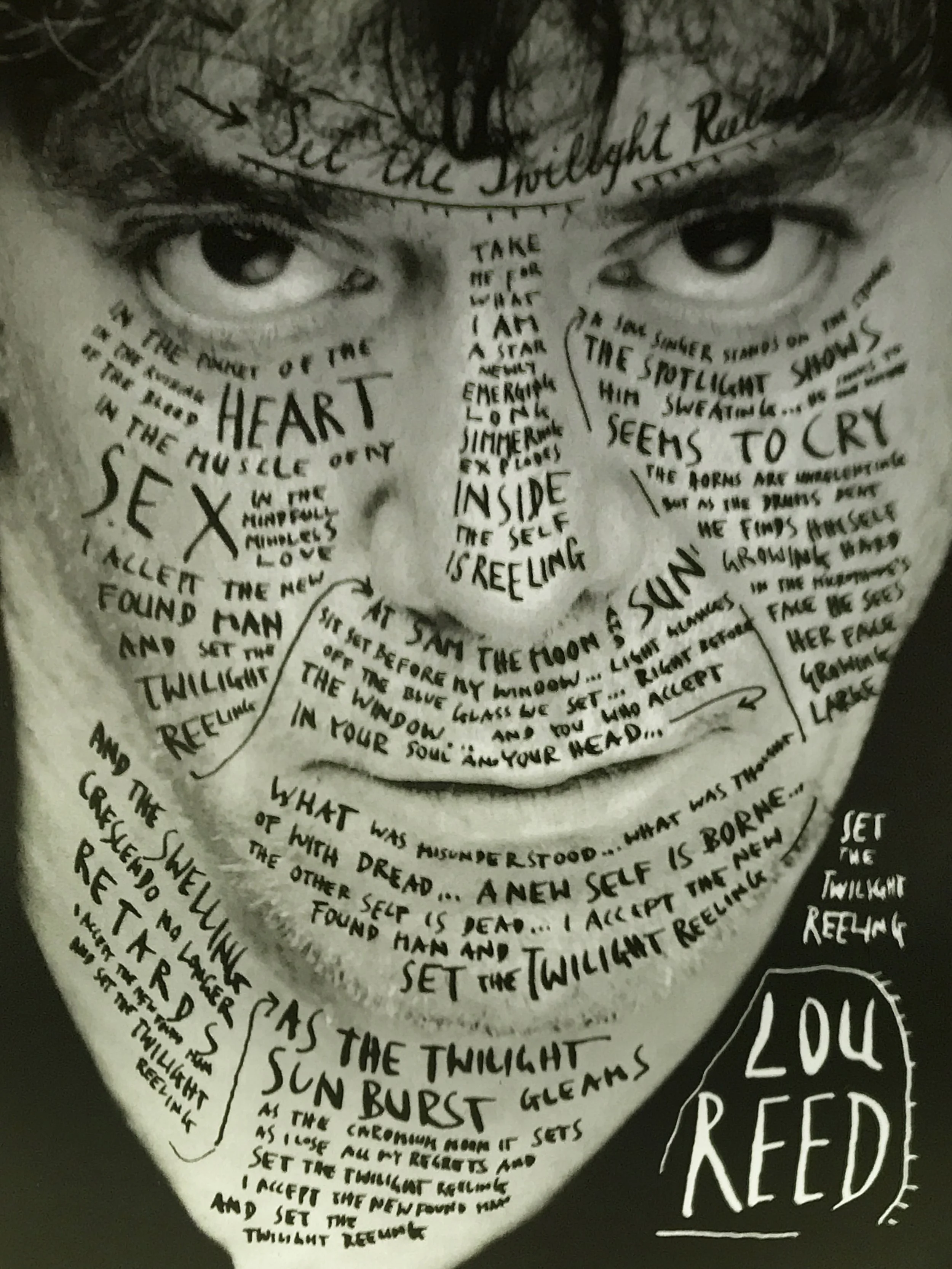

Drawing by illustrator Maira Kalyan @ the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, Amherst, MA.

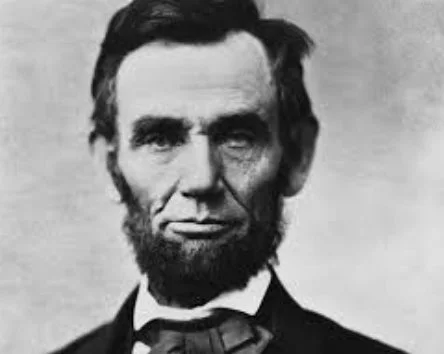

“I don’t like like that man.

I must get to know him better.”

“Cecil Taylor/Andrew Cyrille

University of Pennsylvania

Spring 1975

“If you take the creation of music and the creation of your own life values as your overall goal, then living becomes a musical process.” Cecil Taylor

My introduction to the music of Cecil Taylor was his ground breaking recording Unit Structures. This septet recording done at the legendary Rudy Van Gelder studio in May 1966 featured Eddie Gale, trumpet, Jimmy Lyons alto, Ken McIntyre alto, oboe and bass clarinet, Henry Grimes and Alan Silva on basses, Andrew Cyrille, drums and Cecil on piano. I found this recording in 1969 thanks to the urging of an upperclassman who stated, “Taylor’s music makes Captain Beefheart sound like Mickey Mouse.” I’ll never forget the quote and whether Trout Mask Replica is a gateway drug to Cecil Taylor’s music, I’ll leave that debate to others. Suffice it to say that Unit Structures ranks with Coleman’s Free Jazz, Ayler’s Spiritual Unity and Coltrane’s Ascension as four of the major works in what was dubbed “avant-garde” jazz.

Taylor began his studies on the piano at the ripe old age of five. He went on to study at the New York College of Music and the New England Conservatory. He acknowledged the influence of Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Errol Garner and Horace Silver on his playing, but also the work of composers Stravinsky, Bartok and Stockhausen. Taylor was an aggressive player, whose uncompromising percussive style limited the extent of his audience. He passed away at 89 years old in 2018.

In 1975 he was performing at a very high level and Cyrille had been his mate for nine years, developing a close chemistry. Taylor was on the left-hand side of the stage at his preferred Bosendorfer piano – sitting directly across from Cyrille and his drum kit on the right hand side. They faced one another and not the audience.

Their playing was outstandingly energetic, complex and synergistic and the small audience responded with a standing ovation.

Years later when managing a concert series in Worcester I had the pleasure of booking Andrew Cyrille twice. Once for a solo concert at the New England Repertory Theatre and then for a duet concert with long-time Taylor band mate, Jimmy Lyons at the Piedmont Center for the Arts. Andrew is one of the nicest gentlemen I’ve come in contact with.

“All of us come together because there is a certain kind of life-giving ingredient that goes into the kind of music that we make. Even the source of it, it’s what the American situation is concerned, it has been African and the suffering that we’ve had… But what has happened as a result of what we have learned how to do is that we have provided people around the world another methodology to express themselves, to forgive” –Andrew Cyrille

”